Note: This article was written by Kristi Hayes-Devlin and represents her own thoughts and experiences on baby product safety as it relates to a recent fire in her home. It is not intended to represent BCIA policy or the position of all BCIA members.

Recently, we had a fire in our furnace. It was a sobering and terrifying experience. The most frightening piece is that even though I have given careful and continued thought to fire safety in my home, our smoke alarms did not go off. Since the fire, I have spent many, many hours researching smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide alarms to try and understand what went wrong. You’ll read some of what I’ve learned in this article.

As someone who lives entrenched in the world of baby carrier regulations, compliance, and safety, I can’t help but see a LOT of parallels between my research about smoke detectors and my knowledge about baby carriers. There are hard rules. There are guidelines. There are differences of opinion. There are real-world practices. And there are circumstances that mean the guidelines may need to be reconsidered on an individual basis.

If fire safety education focused more on the real-life truths about smoke detectors, rather than only calling attention to the “perfect” use of smoke detectors, perhaps I would have done things differently. You don’t know what you don’t know. That means there were questions I should have asked of myself and others that I didn’t think to ask.

Since I was a child, there have been fire safety campaigns telling me how to protect myself in a fire. Since I got pregnant for the first time in 1999, I have seen pamphlets, books, videos and commercials with instructions for keeping my family safe from fire in our home. I’ve listened diligently. I’ve gone above and beyond the recommendations. But in the end, although we are fortunate that our home is intact and we are all safe, the instructions I got made no difference to our outcome because our smoke detectors, the first line of defense, did not go off.

Mom. Entrepreneur. Carrier compliance expert. And fallible human being.

In 2004, I started a business manufacturing baby wraps. I have been in the business of baby product safety since that day. I had already been a babywearing parent for 5 years at that point, and I was a mother of three small children, but becoming a baby product manufacturer was a whole different kind of responsibility.

I was vigilant in both roles. I paid attention to the laws and rules. At that time, there was no US standard for baby wraps and the internet was still young. YouTube had not yet been invented. Social media was mostly limited to online forums. E-commerce was growing, but brick-and-mortar shopping was the main way people obtained their goods, including baby products.

Although information was not available the same way it is now, we had thebabywearer.com forums and a large babywearing Yahoo group for sharing information. I connected with other kitchen table manufacturers, who shared information generously. I read everything I could get my hands on to ensure I would only offer safe products through my work. I talked with other manufacturers and with experts in baby product safety.

And as a parent to five children, I have always relied on experts as to inform my parenting choices around safe products — CPSTs, for instance, and other experienced parents. I always read the instructions that came with my baby products. I registered products when there was a registration card attached. I asked for help when something was unclear. I worked to be diligent about my kids’ safety. In fact, you could possibly say I was a bit high-strung about it.

We asked all the questions we knew how to ask, and we asked experts in product safety what we had missed. From those conversations, performance standards for baby slings and wraps was born. Babywearing educators discussed best practices, looking at research in related fields and weighing the different opinions of various babywearing schools around the world.

There was no consensus about what was “right,” but there were strong opinions and excellent academic and practical conversations.

Fire safety

I have taken the same approach when it comes to fire safety. I have smoke and carbon-monoxide detectors installed in my home. You are supposed to replace them every 10 years, and I do that. I use the button to test the detectors (not monthly, as I should, but every few months for sure). I keep the batteries changed. I’ve taught my children how to respond if they go off.

In my kitchen, I have a fire extinguisher, an aerosol spray, baking soda, and a fire blanket. I keep a second fire extinguisher upstairs near the bathroom, and yet another in the barn. I’ve trained my family in how to use them, when to use them, and when to run away.

I even have fire ladders on the second and third stories of my home in case my kids are ever trapped. About once a year, I remind my kids that the ladders exist and review how and when to use them. We have a planned meeting place in case we have to leave the house during a fire.

I feel pretty educated and abundantly prepared, without being totally over the top. We don’t run drills. I don’t obsess about it. And until the furnace fire, I would have said we wre as prepared as we could be.

In spite of everything, my smoke detectors didn’t go off when I needed them.

Its been over a week now since the fire, and the close call we had still gives me chills and nausea when I think about it.

Around 12:30 am, I heard my son’s friend, Seb, yell to me that there was smoke in our kitchen. I ran downstairs, grabbed the fire blanket that’s mounted on my cabinet, and I opened the oven, since there was no clear cause of the smoke. The oven was clear, so I asked “basement?” Seb opened the basement door and it was clear the basement was the issue. I grabbed the fire extinguisher and walked toward the basement door, where thick grey smoke was pouring out, and I looked to see where the flames were. The smoke was thick and filled the basement — I couldn’t even see halfway down the stairs.

At this point, I put down the extinguisher and the blanket, woke my children, and called 911.

We were lucky. Lucky my son’s friend got up to pee and smelled the smoke. Lucky we live two blocks from the fire department. Lucky the fire stayed contained inside the furnace and the firefighters were able to quickly flip the emergency fuel switch. We are lucky the smoke damage is not too extensive. We are lucky our cats are okay.

But the smoke detectors?

The next morning, we came back to the house. The fire department had left around 2am and I spent the night revisiting the evening between snatches of sleep on my neighbors’ couch. Suddenly I realized that not a single smoke detector went off. Not even the one at the top of the basement door, where the smoke was thick and pouring out so much that it filled the kitchen adjacent to the room even before we opened the door.

The smoke had also traveled up the back stairs, leaving soot and odor at the top of the stairs, where another smoke detector is installed. And smoke went into several rooms via the furnace vents.

Not. One. Smoke. Detector. Chimed. It makes me feel sick to think about.

When we came home the next morning, I tested each detector. They are 8.5 years old, so they should have had plenty of time before they needed to be replaced. I pressed the “test” buttons, and each detector chirped loudly and obediently when tested, declaring “we’re working!”

“LIES!” I thought. “You are NOT working. You are horrible and incompetent and should be ashamed to call yourselves smoke detectors.”

I was flummoxed. And I was horrified. It seemed statistically impossible that every single smoke detector would be defective. I looked at them wondering whether perhaps they were all the exact same model? Exact same batch? Could there be a major manufacturing defect that had impacted all of them? The answer was, no. They were not.

Of course I wanted to buy new detectors right away, but now I had a bigger problem — how could I be sure they would work?

Consulting experts

I called the local fire department first to ask them to help me figure out what may have gone wrong. Their answer was that since the smoke detectors were almost 9 years old, perhaps they were coming to their end of life and functioning poorly. I asked, “How often should I replace my smoke detectors?” They answered,”Every ten years.” I pushed back. “You said that you think the detectors may not have gone off because they are almost nine years old, which suggests they don’t actually last for ten years. What is the age they start malfunctioning?” He answered again, “They should last for ten years.” I thanked him for his time and started reaching out to friends, family, and the internet for better answers.

I learned two important pieces of information that would help me understand what had likely gone wrong, and I’m going to share them with you.

- Smoke detectors have several different kinds of technology and each works differently. Some technology alerts to fast-burning smoke, and other technology alerts to slow, smoldering smoke. The affordable detectors most people purchase have only one technology in them.

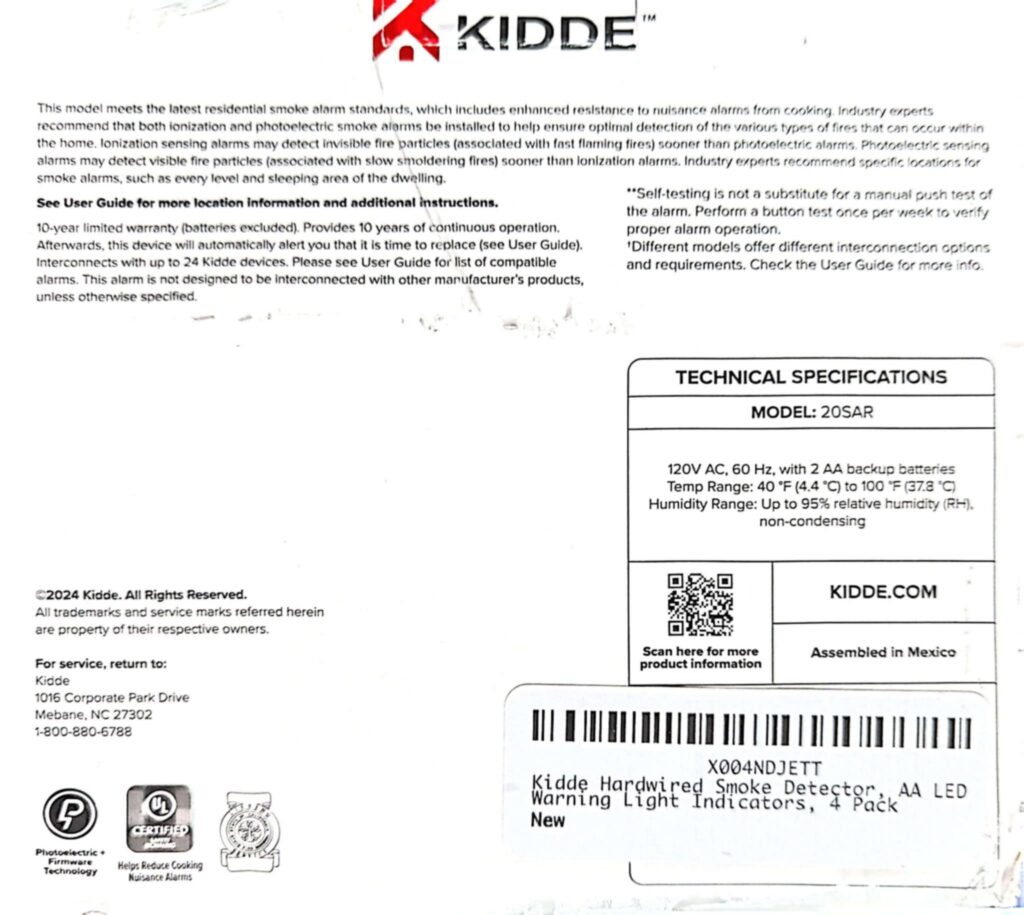

In fact, the Kidde detector I purchased initially has fine print on the box. I took off my glasses and squinted so I could read the tiny text:

This model meets the latest residential smoke alarm standards, which includes enhanced resistance to nuisance alarms from cooking. Industry experts recommend that both ionization and photoelectric smoke alarms be installed to help ensure optimal detection of the various types of fires that can occur within the home [emphasis added]. lonization sensing alarms may detect invisible fire particles (associated with fast flaming fires) sooner than photoelectric alarms. Photoelectric sensing alarms may detect visible fire particles (associated with slow smoldering fires) sooner than lonization alarms.

I then examined the box more. “COMPREHENSIVELY TESTED.” “Designed to the latest UL standard for safety and reliability.” “CUTTING EDGE TECHNOLOGY.”

Then I finally found, tucked into a corner, “Photoelectric+ firmware technology.”

As I read that text explaining, “Industry experts recommend” both kinds of sensors for full safety, I inferred that both technologies were being used. However, on further reading, I found the words “Photoelectric+ Firmware Technology.”

This product, sold to protect my family from fire, was missing an essential component but still meets the relevant standards. And even as someone who understands a fair bit about the technologies, it took me several minutes of careful reading of fine print on all sides of the box to determine that this was not the smoke detector I wanted to protect my family. The actual box for the detector had information that matched other sources: I needed multiple kinds of sensors. The box also told me: this detector had only one type.

2. The specific placement of smoke detectors is extremely important.

I was able to speak to the police chief in a neighboring town, a friend of my mother’s. He spoke with me at great length and looked at photos of my home. In fact, when our fire call first went in, he had looked up images of the home because he was called to bring a ladder truck to our 3-story home.

The chief emphasized that there are two types of detectors, and we may have the wrong kind for the fire we had in the basement. That even though smoke was pouring out the door directly toward the detector, it simply may not have sensed the heavy smoke.

He also asked whether the smoke detector was located near a corner between doorways. And — yes. It is.

It’s placed at the top of the basement stairs, near the kitchen doorway. It’s not in a “dead zone” — rather, it’s on the ceiling a few feet from the door. In the generally recommended location.

However, the chief explained that if a detector is placed near a corner, air can flow between doorways, causing it to miss the detector, so that it doesn’t trigger the sensor.

I had my detectors installed by a licensed electrician. It didn’t occur to me to question the placement of the detector. To my mind, it made a lot of sense to have it where it was, aligned with both the basement door and the kitchen door. But my logic was wrong.

In conclusion, my due diligence was not enough. Even though I had

- certified smoke detectors

- detectors that were not expired

- detectors that had been professionally installed according to the directions

- AND detectors that were tested regularly —

— the smoke detectors had not gone off in the fire.

Tying it back to baby product safety

I spend a lot of time reading and talking about baby product safety and compliance. There are countless organizations and government agencies involved in baby product safety around the globe and each offers a unique perspective. Product compliance is a discipline I personally really enjoy.

Sometimes, the safety of baby products is tested using mandatory standards, the same way my smoke detectors are.

When there are standards written, they are written in consultation with experts from varied fields — human factors, engineering, product labs, parents, industry organizations and brands, government experts, and more. There is a concerted effort made to consider every possible aspect of a product, analyzing hazard patterns and potential misuse, among other factors.

Then, once the standard is created, it’s monitored to see if it’s effective in improving product safety. Hazard patterns continue to be monitored and changes are made when necessary.

Not only are there standards for the products themselves, but there are task groups and nonprofits and government organizations and professionals and countless others who research, observe, discuss, and share information about how best to USE baby gear. From this comes campaigns about safe sleep, campaigns about carseats, campaigns about leaving strollers uncovered, campaigns about choking hazards, and many other safety standards.

Many of these topics are controversial. And even when they are not what we might CALL “controversial,” there is often controversy or disagreement between experts on what constitutes “best practice.” Safe sleep and cosleeping, for example, are topics that can divide a room into factions quickly. A lesser discussed topic is whether small infants who are carried routinely on a caregiver’s chest also require traditional “tummy time” for motor development. Well-educated professionals can make evidence-based arguments that contradict one another, and as parents and as professionals, we have to sort through the details and form our own opinions based on the evidence and our experience.

Baby product standards are imperfect, but they are effective

I don’t know about the history of smoke detector standards, but I do know about the history of US baby carrier standards.

When ASTM was first creating the sling standard, they looked at the main hazard patterns reported through the CPSC and other public health groups.

The main hazard for sling carriers was suffocation. Although deaths were rare, when they occurred it seemed to be related to positioning and feeding. The secondary hazard was falls. These were much less frequent and mostly attributed to one particular brand of baby carrier, so not a general pattern across brands.

The standard was written with those hazard patterns in mind. Since finalizing and implementing the carrier standard, we’ve seen a significant decline in the number of deaths that occur in infant slings — generally fewer than one per year. The standard has been extraordinarily impactful in improving the safety of these important products. Of course, the ideal number of tragedies like these is zero. But when I view the data and compare it to other durable nursery products, I feel quite proud of the standard we created because it had a meaningful impact, almost completely eliminating deaths in baby carriers within the US.

We saw something similar with soft carriers after the publication of that standard in the early 2000s. The primary hazard identified in that product were falls and skull fractures. After the standard was created, there was a significant reduction in the number of falls from these carriers. A secondary hazard pattern of suffocation was identified, similar to slings, and the changes made seem to have had a significant impact on reducing that hazard pattern as well.

Limitations of standards and testing

Although infant products, including baby carriers, are safe and important tools for child-rearing, my fire was a stark reminder that even with vigorous care and attention to detail, life is not as straightforward as rules and standards.

Testing is only one aspect of baby product safety. It’s an important aspect, but it can’t solve everything.

My smoke detectors, which were tested in accordance with a standard, were not the right product for my needs. Marketing led me to purchase a specific style of smoke detector, but it did not detect the smoke from my furnace.

Caregivers of infants also have to have to wade through brands and marketing and public messaging and endless advice to choose the right products for their needs. They can’t rely on standards alone to make these decisions. Let’s consider baby carriers, for instance. A handheld carseat meets rigorous standards both for car safety and as a durable nursery product for carrying children. Handheld seats and babywearing devices and bicycle seats are often lumped together as “baby carriers” in public incident reports and public opinion articles, as though they essentially the same thing.

The truth is, it is widely believed by experts that handheld carriers pose significant challenges when it comes to keeping an infant well-positioned outside of a car. There is a great deal of research and many public safety campaigns that describe these challenges. If you are reading this post, you likely agree that a baby sling or soft carrier is a better tool for carrying babies, as they are specifically designed with a focus on safe positioning outside of a motor vehicle.

Carriers allow parents to keep their babies “visible and kissable (r)” with baby’s head on an adult chest where their breathing, temperature, mood, comfort, etc. can be easily monitored. There is no safer place for a baby than under the direct supervision of a caregiver.

However, even with a quality carrier that meets all relevant safety standards, parents must read the instructions for their infant products, and ideally, the instructions will be high quality and easy to follow. As with all infant positioning devices, in rare circumstances, covering a baby’s face or positioning them incorrectly can lead to tragedy. The mandatory standards ensure that every baby carrier manufactured in the United States and many other parts of the world carry this warning prominently, as well as a warning that baby carriers can pose a fall hazard.

However, instructions alone cannot ensure correct use of a product. Instructions certainly cannot cover all the individual circumstances of babies and caregivers who will use a particular product.

I read the instructions for my smoke detectors, thoroughly, and they still did not sound an alarm when faced with heavy smoke. There were things that weren’t or couldn’t be included in the instructions. And even if the instructions had covered every possible thing in detail, each home and its layout is slightly different, just as each baby and its body is slightly different.

This was my BIG THOUGHT. The thing that spurred me to write this blog post. We, as educators, manufacturers, healthcare workers, standards writers, and parent support people focus on what we can do. It gives us a sense of security. But there are elements we cannot design for or plan for, no matter how careful the engineering or education.

We don’t always know what we don’t know.

Individual circumstances

We must always protect babies’ airways. This is a universal, incontrovertable truth.

Nearly every baby who has passed away while being held in a carrier (which happens too often, but on average less than once each year worldwide, as far as we can tell) has had their face obscured from the person who was carrying them. This is another truth based on data and facts. For this reason, we recommend that a caregiver be able to see their baby’s face at all times.

Of the small number of fatalities in baby carriers, an outside percentage occurred in babies

- who were born early or at low birthweight

- who were being fed or had recently eaten

- were under 2 months old

- had respiratory illness or conditions

For this reason, we warn parents that babies in these categories are at higher risk.

Prior to 2010, an outsized number of fatalities in single-shoulder sling carriers occured in babies being held in a reclining position. Nearly 25% of these occurred in what we now describe as “bag slings,” which many of us in the industry believed were inherently unsafe even while the CPSC allowed their sale. Others occurred in pouch-style slings or large, padded slings with small straps for adjusting, in which babies could only be carried in a reclined position. Because of this, we recommend caution when reclining babies, carefully supporting babies’ backs and heads in a snug, neutral position, and repositioning after lowering babies for feeding.

We must ensure that the carriers we use for babies, especially very small babies, are designed to contain them safely so they will not fall and fracture their skulls or otherwise sustain injury. This is another incontrovertible truth that is backed up by years of incident data.

There is evidence that in their first few months of life, babies whose legs are held close together for several hours at a time may be at higher risk of hip dysplasia. This is not a concern when a baby is carried for short periods of perhaps an hour or less, and there is still some question whether the evidence shows a true risk. However, we generally recommend that baby carriers and other infant holding devices support a baby’s thighs in a spread position when carrying them for several hours. One research study suggests that 100 degrees is an optimal position for the hip, but many believe that a baby’s legs must just be slightly spread and their thighs generally supported during the first few months of life. For this reason, many organizations and babywearing educators suggest that parents of infants under 6 months avoid carriers that leave a baby’s legs dangling straight down and unsupported.

Aside from that, there are countless opinions on what is “right” and “wrong” in babywearing safety. Often, these beliefs are shaped by online parenting groups, by cultural beliefs, by values held closely by a regional community, or by personal experience. However, here is what we know for sure, based on data.

We must protect the airway and protect from falls. Always.

We should use extra care with small or young infants, babies with respiratory infections or conditions, when feeding babies in carriers, and when carrying babies in reclined positions.

And we should take care with babies’ hips when carrying them for long periods of time in their first 3-6 months of life.

After that, things get muddy. There are experts who will tell you it is dangerous to use baby carriers or slings in the first three months of life. There are experts who will say you should never allow baby’s legs to fall lower than 100 degrees because it is dangerous. There are those who say you should never feed a baby in a carrier. There are those who say it is dangerous to use certain clothing while carrying, or to carry in the sun, or NOT to carry in the sun. There are those who say you should not use carriers while sitting or wading.

There is also evidence that carrying small babies can be life saving for countless reasons, which would mean that following advice to never carry small babies would actually increase infant fatality. There is evidence that overall, feeding babies in carriers can increase breastfeeding success and keep babies safer. There is evidence that parents who feed their babies in carriers might otherwise use a propped bottle in an area where there is no adult supervision while they tend other necessary tasks. There are those who say using a carrier in water is safer than just holding a baby in arms.

These are all topics that can and should be discussed — but focusing on them dilutes the real safety issues.

And in truth, many of these issues are questions of individual situations. For some people, it may be safer to hold a baby in their arms in the water, while for others, using a carrier will be a safer choice.

While generally a carrier will support a baby best if it is snug and secure, depending on the specific carrier and situation, if a parent is sitting at a desk working or using a wheelchair, it may be best to loosen the shoulders of the carrier to allow baby to remain in a more neutral position.

While there are guidelines about hip positioning and carrier positioning, some parents or children will have physical differences, medical devices, or other circumstances that mean following popular “rules” is suboptimal for them or their children or, in some cases, may even be dangerous.

My smoke detectors may have been impacted by very specific properties of the airflow in my home, and I will consult with experts to determine whether they should be moved and how they should be moved to meet my specific circumstance. There are rules I should never break in terms of my smoke detectors and fire safety. Then there are aspects that need to be decided and tailored to my individual situation.

The importance of community in fire safety and in baby product safety

Ultimately, it will not be standards alone, expertly crafted instructions, babywearing educators, certified electricians, childbirth educators, physicians, or any other single thing that will keep our children safe.

It can be painful to acknowledge that life carries risk beyond our control. Tragedies have shattered families whose babies were perfectly positioned in holding devices such as swings, cribs, carseats, carriers, or bassinets. To families who did everything objectively “right.”

The North Eastern Ohio Fire Prevention Association says that over half of all smoke detectors fail. That number is terrifying. Many families who have detectors fail, like me, worked hard to ensure everything was “just right.” They thought they were safe. But without nuanced discussion in public forums that acknowledges real-life differences in homes, fires, and families, people are not able to ask the questions and make the adjustments that keep their families safe.

Fortunately, the “failure rate” for baby carriers that are worn on the body is close to zero. The failure rate for other kinds of carriers, such as handheld infant carseats, is a different matter, but I would like to focus on slings, frame carriers, soft carriers, and similar on-body carriers.

An overemphasis on “perfection” (whatever that is) when discussing babywearing leaves no room for nuance and for questions and for individual bodies and circumstances. The word “dangerous” should be reserved for times when there is actual danger. The use of bag slings. The use of carriers that are too big to hold baby securely. Holding a young infant in a carrier that obscures their face from the caregiver. A small baby whose head is tipped forward, backward, or sideways at an angle that may close off their airway.

Using the word “dangerous” for every situation we believe to be suboptimal dilutes the important messages. It takes away confidence and autonomy from new parents. Frequently, I’ve heard from parents who feel so discouraged by all the “rules” that either they or their partner refuse to use a baby carrier at all, which means their baby doesn’t get to access the health benefits and sometimes life-saving effects of being worn in a carrier. It means their babies will probably be held in other devices, many of which don’t offer the inherent safety and benefits of on-body baby carriers.

What is ideal for one baby may not be ideal for another. A baby who is hypermobile, or who has respiratory issues, or who has low muscle tone, may require a different kind of positioning, different kind of monitoring, or a different kind of device.

Parents may have physical limitations that prevent them from getting the “perfect carry.” Those parents can still achieve a SAFE carry that protects their child’s airway and holds their baby securely. We must leave space for caregivers who don’t do things “perfectly.” In some cases, what is “perfect” for most families may even be contraindicated for someone with particular physical traits. There must be space for nuance, and there must be space for questions, if we are to achieve our goal of increasing families who are reaping the incontrovertible benefits of carrying babies on our bodies.

Universal truth in baby product safety

Sometimes, we need a variety of experienced people from our community to weigh in with advice. Because the universal truth in baby product safety is that rarely are there universal truths in parenting. Whatever the “rule,” you can almost always find some babies or parents who are an exception to that rule.

Yes, all babies must breathe freely and have their bodies protected from injury. But differences in physiology and health needs sometimes mean the “right” way isn’t “right” for some children — we must leave space for this truth.

For individuals

As with fire safety, we should do what we can as individuals to protect ourselves and our families. Have extinguishers and smoke detectors and, ideally, fire ladders. Test everything to ensure it’s functioning and safe, and have a plan for remediation if something goes wrong.

But ultimately, we are humans living in an imperfect, asymmetric, varied world. We don’t all know what questions to ask. We may not have the means to purchase collapsible fire ladders or replace all of our smoke detectors every ten years. We need to focus on the most important things.

Each of us has different risk factors — the air quality in our neighborhood; the particular angle and mobility of our baby’s hips; our own physical differences and disabilities.

Manufacturers and professional educators must continue to do our due diligence — ensure our children’s products have been tested for safety and come with instructions we can understand. But we also need to keep asking questions.

If you see someone you believe is doing something “dangerous?” Ask yourself what the danger is. Does it fall into a clear and immediate risk of fall or suffocation hazard or is it just what you consider “suboptimal?” Then, if you feel a responsibility to say something, approach that parent assuming that they are capable, competent, and loving, but that perhaps they were up all night with a colicky baby and a sick toddler. Perhaps they are struggling with postpartum depression and a well-meaning elderly neighbor giving them nonstop parenting advice and perhaps a single parent. Approach them with care and caution and kindness.

If you are a babywearing parent? Know that there are many people on the internet with a great deal of knowledge, and even more who carry a great number of opinions. They are usually well meaning, and sometimes they are managing their own insecurities by trying to be helpful. They will tell you exactly what they believe you are doing wrong with your carrier and how they think is “right.” You can listen to their advice, but check the information for yourself. Ask if it’s relevant to you and your baby. Ask how it can be better. Get a second opinion. Listen to your baby’s breathing and watch for signs of comfort. Protect your baby’s airway.

And remember that even experts can get it wrong. Like the electrician who gave careful thought when placing my smoke detector — the fire chief thinks that its positioning is why it didn’t go off. I can’t test that theory. The chief may be incorrect in his assessment. Perhaps the electrician was correct in deciding that was the best place to put the detector and there’s another reason it didn’t go off. I’ll likely never know.

For brands, importers, educators, and other professionals

When it comes to babies, there is a legal responsibility and also an ethical responsibility to only offer products and information for sale that hold safety front-of mind.

This is more than just complying with regulatory standards. This means conducting an internal risk analysis to look for where things might go wrong with your product or information. This means having a clear, written plan for staying up-to-date on standards and best practices. This means having a written compliance plan and, if you manufacture or import products, a solid plan for dealing with complaints, safety concerns, and product recall.

It also means regularly reviewing your instructions and marketing materials and consumer-facing communication.

Do not take your responsibilities lightly. And remember: even if you are thorough and careful, there may be questions you’ve forgotten to ask. Organizations like the BCIA can help you think of these things pre-emptively, but you need to approach your work with nuance and curiosity.

What I hope you’ll take away from this

First, please check your smoke detectors and fire extinguishers. If my son’s friend had not woken up at 12:30 am and smelled smoke, I don’t know how the night would have ended. It’s horrifying to realize that although I did everything “right,” the alarms did not sound.

Second, hold the idea that there is no simple standard that holds all the answers. Your family, your baby, and your needs are nuanced. That is a large part of why the BCIA exists — so that you have access to safe carriers to meet your particular nuanced needs.

And if, when using a carrier or any other baby product, you find that something doesn’t feel right in spite of reading directions, etc, consult an expert. Perhaps two if you need to. Because you don’t know what you don’t know. You can use our member directory to start your search for a babywearing educator.

If you are a brand? Recognize that simply testing to the standard is not your whole responsibility. Testing is one piece of baby product safety — continually listening to experts varying opinions is important. Having a recall plan in place is important. Ensuring your instructions are easy to follow is important. Having clear channels through which your customers can offer feedback is important.

Baby product safety is nuanced and ongoing, like fire safety. And both are important. I am grateful to be part of both local community to hold me after a disaster in my home, and of my greater babywearing community that has supported me as a parent since before my first child was born. I’m grateful for this community that has always helped me ask the questions I didn’t know I should ask — to help me see what I don’t know.

Want to learn more about baby product safety — specifically, baby carrier safety?

You might enjoy this article explaining baby carrier compliance for parents and caregivers preparing to purchase a carrier.